Collecting Data Honestly

The Big Question

Let’s start with a question I typically ask end-users.

Do you know if your organization looks at your web browser history?

I want to clarify that I am not asking them whether or not the company collects web browsing history. I am asking them whether they know, with 100% certainty, whether the security team is or is not. It is one thing to know whether your organization can view your browsing history, and another to know if they do. Also notice I didn’t ask them if the organization usually looks. One person, looking once because they were curious, is looking.

After making these clarifications, it is my experience that there are three camps of people who can still emphatically answer “yes.”

The Three Camps Who Say “Yes”

The first camp are the folks that definitely know they are being surveilled. They know because they have seen their peers reprimanded or even fired because of their web browsing history. In these organizations, the leadership is all too proud to communicate the veracity and insidiousness of the surveillance because they see it as a deterrent to people slacking off, stealing from the company, and other assumed nefarious activities their so-called “trusted” employees might be getting up to.

The second camp are the folks who know they are not being surveilled because the company has no security or IT tools or policies. On their first day they opened up their laptop, fresh out of the packaging, and did not have to install any company mandated security tools, management profiles, or agents. They work from home on their own Wi-FI, and they never need to connect on a VPN. The great irony here is that these users might be ignorant there are capabilities like Apple’s Device Enrollment Program (DEP) that are able to put Macs under management fresh out of the packaging directly from Apple’s warehouse!

The third camp are the folks who can answer “yes”, because they know exactly what tools are installed on their devices and what the tools are capable of collecting. More importantly, they know they can independently verify how the security and IT team is using these tools in practice. They know if the security team is looking at their web browser history because the tools the security team uses require them to know. These are people who work for companies that practice Honest Security.

The Folks Who Say “No”

But what about the most common case, when end-users answer “no?” If you don’t know if your organization looks at your web browser history, why don’t you know? How can you find out? Who do you reach out to to find the answer? Do you feel empowered to ask these questions without reprisal?

If you pushed your organization to adopt Honest Security, this conversation will be easy to have. If it hasn’t, then users are stuck in the dark, not knowing what tools and security practices are being used on devices. You may discount the psychic toll this has on end-users, but it’s very real and it can negatively influence their behaviors and decisions, in the same ways excessive surveillance can when implemented at a nation-state scale.

Informed Consent

Informed consent is a term used by the medical community. In the United States (and likely abroad), if you’ve ever undergone even a minor procedure that carries some risk, a medical professional likely walked you through those risks, even if their probability is infinitesimally small. Not only did they do this verbally, they likely gave you a printed document that could not be adulterated by the medical staff.

Practicing informed consent in medicine is obviously the right thing to do, but it’s not something that organically came to be. Its codification into Federal law is the result of hard won litigation by people permanently harmed by medical procedures where they felt they were not adequately informed about the risks. Before informed consent, those infinitesimally small risks were buried in legal documents with 8pt font. If discussed verbally, they were diminished by doctors pushing for specific outcomes that they thought were best. While withholding information may feel like you are just making choices clearer for people, it’s essentially lying by omission, and this approach was dishonest enough that laws needed to be created to protect people from harm.

Switching back to modern endpoint security, the lack of informed consent continues to be a key feature. Security team members feel that the statement in their employment agreement, or the one bullet on slide 34 of last year’s security training powerpoint are sufficient forms of consent.

In Honest Security, informed consent should take place in moments when there’s a chance lack of consent could damage the trust between the end-users and the security team. An example of a situation where consent should always be obtained is the deployment of software that collects facts about user devices. As benign as these facts may be, users have the right to understand and control this process.

Example: Onboarding

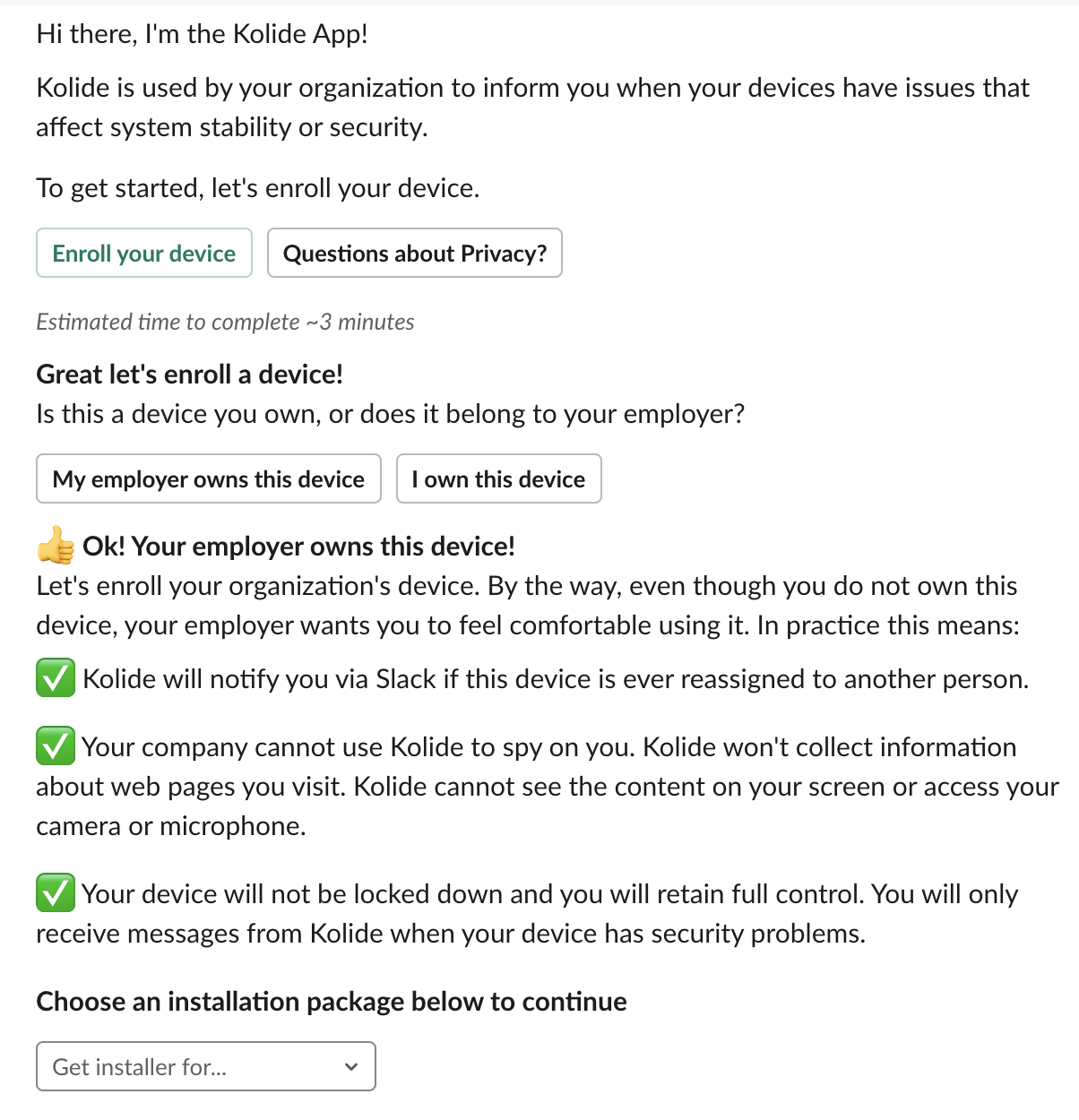

Kolide’s product obtains this consent process through an enrollment workflow in Slack (pictured below).

You’ll notice a few things here. We aren’t rolling out the endpoint security software silently in the background and informing users after the fact. When embracing a consent based approach, the end-users are the ones who actually download and install the package. They feel in control because they are in control.

There are some additional situations that Honest Security requires consent for each instance. These include the following:

- viewing or transmitting the Geolocation of a device,

- reading the contents of files in the user’s directory,

- and remote-locking/erasing personally owned devices.

While these situations are obvious choices to require consent, your organization may feel they aren’t enough. The consent requirements should be fine-tuned with input from the privacy sensitive individuals of your organization, the above only represents the minimum bar that every organization should reach.

Transparency

It’s not practical or healthy to ask for informed consent for every single action. Imagine having surgery and you having to consent to every move they are going to make, every medical device they are going to use, and review every possible contingency plan. This is a waste of everyone’s time and creates permission fatigue that results in the blanket consent for any task.

Where informed consent is inappropriate, transparency is essential. Many security products feature audit logs, but those audit logs are rarely readily accessible to end-users who stand to lose the most when a bad-actor abuses their access to their work device. In order for the automatic accountability of transparency to apply, it must be consistently applied to all mechanisms available to obtain data.

Example: A Privacy Center

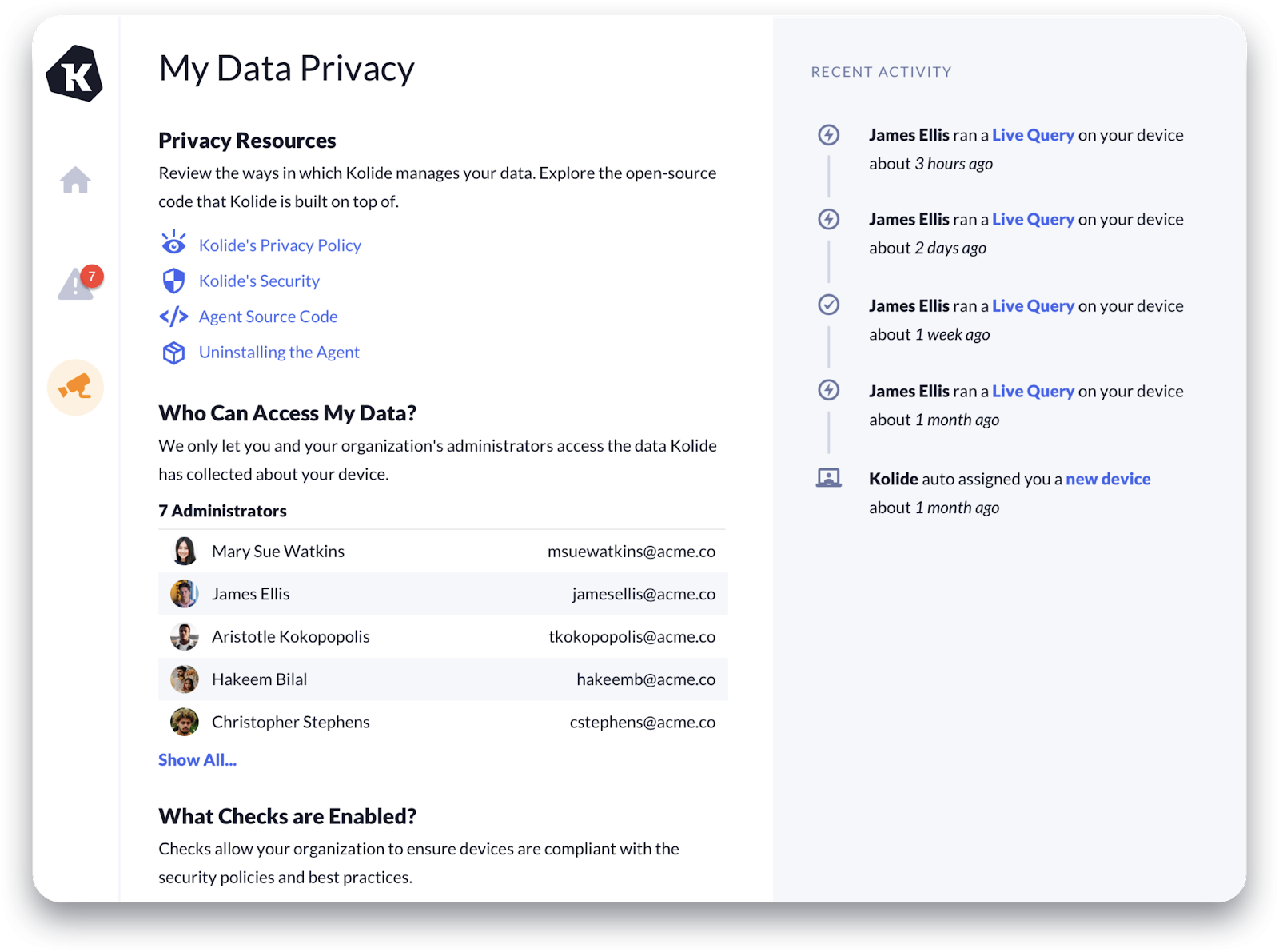

At Kolide, all users have access to a Privacy Center that allows them to scrutinize how the access they consented to earlier is being used by the various members of the security and IT teams.

In the absence of transparency, some of your more worried users are left to assume the worst, that the access is being abused or that they are being unfairly monitored. Can you blame them? In the post COVID-19 era, the news is littered with human interest stories about evil bosses abusing computer management and IT software to spy on their employees.

As many security teams know, the reality is much more boring. Why not show them the truth? It makes everyone (including the security team) feel at ease.

The Insider Threat

The most common argument I see against transparency is that it gives bad-actors within your organization an advantage. The rationale is that an insider threat might be able to identify gaps in the security team’s detection capabilities and systematically abuse them to complete their mission. I disagree. As we all know security through obscurity rarely works. Also, it’s much more likely that this transparency and regular contact will instead serve as a deterrent. Unlike end-users who are making unforced errors, malicious insiders are afraid of being caught. The more interactions they have with a team practicing Honest Security, the more uncomfortable they will get.

Part of Honest Security is trusting end-users because they are our colleagues. If you build a dystopian and cynical security program born out of fear, mistrust, and suspicion, then you will inevitably make your fellow-employees your enemies. The positive working relationship we are advocating for in this guide cannot exist under such a program. Only you can judge if that trade-off is ultimately worthwhile.

The Importance of Ground Truth

In order for Honest Security to function properly, it must have highly accurate facts about devices, organizations, and most importantly people. These ground truths allow Honest Security to confidently make correct security decisions/assertions and deliver them to the right people.

The “ground” in ground truth indicates it is information provided via direct observation by a trusted solution. This is necessary for several reasons:

- Accuracy of the data is essential to the Honest Security mission. Honest Security practitioners must be able to immediately and directly correct any inaccuracies. It is unacceptable for the system to draw incorrect conclusions from bad data sources. Relying on substandard data puts the credibility of Honest Security at risk.

- As mentioned earlier, in order to be honest, ground truth must be collected with informed consent. Dishonest security solutions do not care if their data sets are ill-gotten as they never rationalize data collection with end-users.

- Honest Security should be accessible for businesses at any stage to implement. Increasing the total cost of ownership for early stage businesses by forcing them to buy additional products to power Honest Security’s core mission is unacceptable.

In the absence of these positive guiding principles, dishonest security looks to amass as much data as possible, in unfounded preparation that its value can be fully realized later.

Honest Security asserts that the list of ground truth to collect is solely driven by the needs of the education and compliance mission. This assures that Honest Security solutions can always fully explain to an end-user why specific data is needed and how it is used.